This week, in part 2 of his article on Mag Léna, John Dolan covers another split and a far more important event than a battle in Mag Léna. This synod was just one matter in a significant dispute between the Irish or Celtic church and Rome in the 7th and 8th centuries.

Background

The expansion of the Christian church out of Jerusalem was based on the infrastructure and administration structures of the Roman Empire. Building Roman roads throughout the empire to assist military and trade movement allowed Christians to expand and base themselves in cities. Christianity was just one religion that was practiced in the empire. Christianity developed in an urban setting with bishops based in cities.

Gildas dates the arrival of Christianity to England by 1st century. Bede tells us that in 156AD King Lucius of the Britons sought Christian instruction from Pope Eleutherus and that ‘this request was quickly granted, and the Britons received the faith and held it peacefully in all its purity and fullness until the time of Diocletian’. But by 303 – 312AD Diocletian was persecuting Christians in England by blaming them for military failures. By 380AD Christianity was recognised as the official religion of the empire.

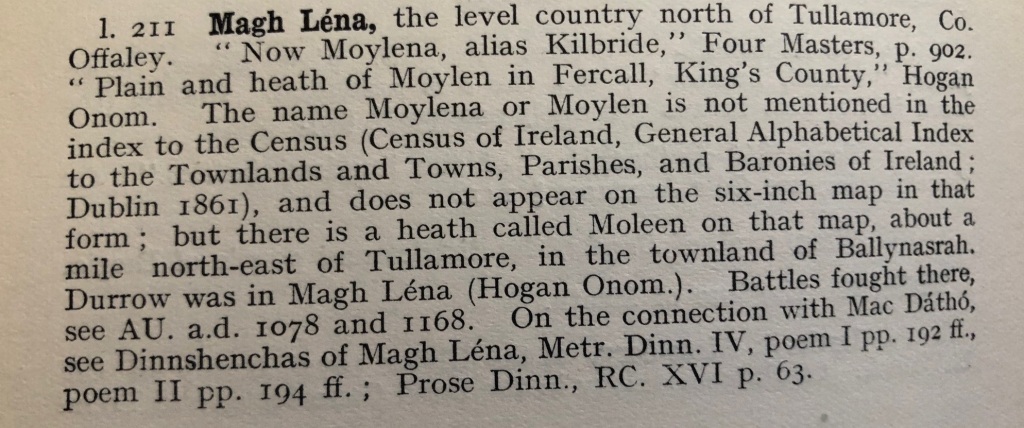

Where was Magh Léna?

In the first hundreds of years the church, now based in Rome, had difficulty agreeing and establishing church doctrine and ritual. Many Councils were called in various locations across the Empire but without a formal process for approving doctrine resulted in attendees returning home where the issues were further thrashed out and local decisions approved. This resulted in many accusations of heresy and subsequent excommunication.

Attempts to resolve these issues were addressed at a variety of Councils such as Arles (314AD), Nicea (325AD), Sardica (347), Rimini (359AD), Ariminum (360AD) and Mansuetus (461AD).

The Irish church development

There was no single, homogeneous church organisation in the early Irish church, sometimes called the ‘Celtic’ church.

The church in Ireland and Britain developed differently from Gaul and the rest of Europe. Communications became much weaker with the fall of the Roman Empire. The church in Ireland and England was found to be using older systems of church ritual that had been passed on verbally.

From an administration point of view the words ecclesia and parochia were applied differently in the insular church compared to Europe. Ecclesia in Europe was understood as a bishop’s church in a city; however, Ireland had no cities and the word was applied to wherever the bishop resided urban or rural, church or monastery. Parochia in Europe was a country church with several priests and under a bishop’s authority. In Ireland parochia is much discussed with little agreement. Charles-Edwards’ definition is that of a group of daughter-houses controlled by an abbot in a mother-house; the authority of some abbots could overshadow that of a bishop.

Churches in Wales and Cornwall followed the Irish organisation and rituals.

The Christian world regarded the death and resurrection of the Saviour as the two supreme events of the year. The calculation of the date of the resurrection was a matter of great importance to the church. But this was not a simple calculation. Jesus died on the feast of the Jewish Passover which was celebrated on the fourteenth day of the month of Nisan which was also the day of the full moon of the first lunar month of Spring. The Jews employed a lunar calendar, with a mean year of 354 days.

A number of current religious celebrations had originally been aligned with the Jewish Passover. If one looks at how close these religious events were celebrated this year 2023, we see how close they still are to one another – the Jewish Passover (5 – 13 April), the Roman Catholic and Protestant Easter (9th April), the Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Easter (both 16th April) and the feast of Ramadan (March 22 – 20th April).

The Roman Empire started to fail and the Jewish state came under hostile enemies, the Christian church moved westwards and began to break away from dependence on the calendar of the Jews. Between 200 – 600 AD Easter was littered with rival tables; many tried, found wanting and discarded. In 444 AD Pope Leo commissioned Victorius of Aquitaine to produce a new table for calculating Easter. This resulted in chaos, it was accepted in Gaul but ignored in other parts of Europe.

A recorded dispute was between Victor, bishop of Rome (189 – 198) and the churches of Asia Minor led by Polycrates, bishop of Ephesus over the date of Easter. Victor chose to excommunicate the Asia Minor churches which had ‘decided to hold the old custom that was handed down to them’.

Irish colleges taught computus, exegesis, canon law, grammar, penitentials, hagiography, Latin and Greek. Computus refers specifically to the calculation of time. Three student textbooks on computus survive that use the question and answer approach to teaching the subject – what is time? what is a second? what is a minute? what is an hour? etc. The textbooks followed a structure that Isodore of Saville had laid down in his Etymology, book 5.

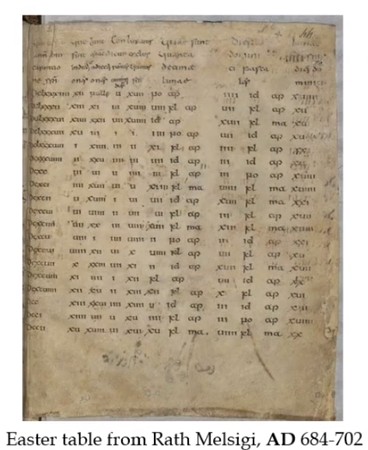

Easter Table from Rath Melsigi

Two events triggered the dispute into an intense period of conflict over the Easter celebrations. In 630 (or 632) Pope Honorius wrote to the Irish church on the Easter question, he claimed he had heard from Gaul that these malcontents from the edge of the world (Ireland), were now sponsoring an older version for the calculation of Easter among other issues. He threatening excommunication if they did not conform to the Roman way of calculating Easter. As a result of this letter the southern churches in Ireland were favourable to the Roman cycle from about 632AD. This letter is likely to be the start of the split in the Irish church which Cummian attempted to resolve at Mag Léna. However, the northern church in Ireland, along with Iona and the Northumbrian churches retained the previous system.

The second was the Columbian conversions and adoption of Irish practices in Gaul that had been noticed in Rome. Columbanus of Bangor, Co. Down arrived in Gaul as a teacher in 590AD. Within a short period, it became evident that there were many points of difference and friction between the teaching and rituals of the Irish churches and those practiced in Gaul. These included liturgies, method of administering baptism and other sacraments, method of episcopal ordination, tonsure and the whole system of church organisation and discipline. Columbanus wrote angrily to Pope Gregory I about the continental table for calculating Easter. He damned Victorius’ table by declaring it dismissed by Irish computists and scholars. In 603AD he wrote again to the bishops of Gaul recommending the Irish calculations.

The Synod.

The Irish church held a synod at Mag Léna Offaly, the date is uncertain but probably 630AD. The resolutions of the synod are lost. The synod was not an all-Ireland synod. The southern churches were more disposed to the Roman calculation for Easter and attended in strength at Mag Léna.

According to the Triads of Ireland the Bishop of Emly headed the list of clerics gathered at the Synod of Mag Léna. Cummian lists the principal participants at the synod as ‘the successors of our first fathers: Bishop Ailbe of Emly, Ciarán of Clonmacnoise, Brendan of Clonfert, Nessan of Mungret and Lugid of Clonfert-Mulloe’. Cummian was abbot of Durrow and regarded as a fer légind (head master/academic). There is no record of any of the local princes attending the synod.

Cummian claims that there was unanimity in accepting Victorius’ calculations but a malcontent later split the congregation with some accepting, others did not. He describes this split as follows ‘not long after, there arose a certain whited wall, pretending that he maintained the traditions of the elders, who in place of unity caused dis-unity, and in part made void what was promised’. Cummian does not name this whited wall, it was likely to be a senior cleric from one of the major monasteries. The result of the synod left a lot of bad feeling.

Following this major disagreement Cummian had no option but to refer the dispute to Rome. A mission of monks was sent to Rome, who found that the current Roman Easter method was not that used by the Hebrew, Greek, Scythian or Egyptian churches. Upon their return the southern churches decided to conform to the Roman Easter, however the northern churches, along with Iona decided to retain their previous calendar.

The calendar for religious events used in Europe was eventually established by Pope Gregory in 1582AD but not accepted everywhere.

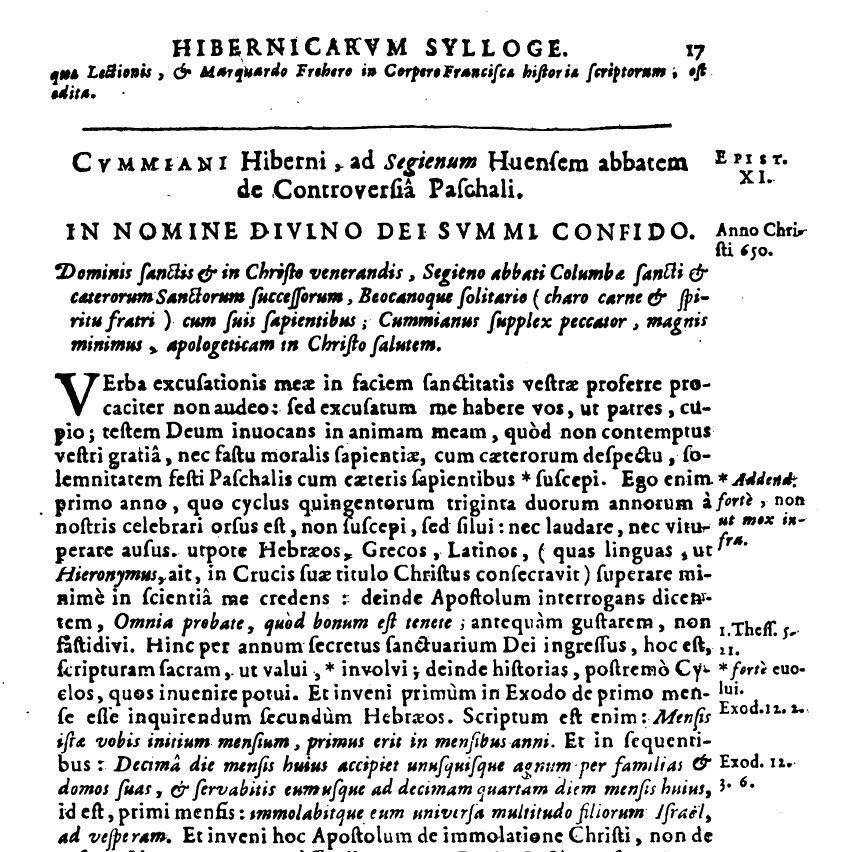

Cummian’s Letter De Controversia Paschali.

Cummian’s Letter is the most important output from the Synod. Alfred P Smyth suggests that Cummian wrote his Letter at Durrow as he was abbot there.

It took a year while Cummian considered his next step. He then wrote a letter to Segene mac Fiachnai, abbot of Iona in response to Segene’s earlier letter concerning the southern Irish churches. He proposed the adoption of the Victorius of Aquitaine cycle which he believed was then in use in Rome.

Two 9th century copies of the Letter survive and prove that Irish computists had achieved a high standard of learning. The Letter gives a detailed understanding of the Irish view of the calculation of Easter starting with how the Hebrews calculated the date of their Pasch (Passover). He tells us that Patrick brought his own formula into Ireland, details both the Victorian and Dionysian approaches and lists 10 different Easter cycles known in Ireland.

He was worried that ‘the Hebrews, Greeks, Latins and Egyptians who are united in their observances of the principal solemnities, or an insignificant group of Britons and Irish who are almost at the end of the earth’ may be out of step.

As a fer légind Cummian was able to support his arguments with quotes from the Vulgate and Vetus Latina Bible and added commentary by Augustine, Jerome, Cyprian, Ambrosiaster and Gregory the Great. He included extracts from the Canon Law of the time, ecclesiastical history and decrees from a number of synods.

The letter is undated but is suggested for 632/3AD. Archbishop Ussher made a copy of the letter from one in the Cotton collection that is now lost. Ussher’s copy can be found in his Sylloge.

First page of Cummian’s Letter from Archbishop Ussher

The full text of Cummian’s Letter is available from the UCC CELT Project at https://celt.ucc.ie/published/T201070.html.

Bede and Synod of Whitby 664AD.

The account recorded by Bede in his Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Angelorum is the only significant account of this synod; he does not provide us with a date. The Northumbrian King Oswald had been exiled to Iona, converted and learned the Irish approach to church rituals and the Irish calendar. Forty years after Augustine had based himself in Canterbury Oswald sent to Iona for a bishop to teach and administer to his people. Iona sent Aidan and he was given the island of Lindisfarne. Oswald, who could speak Irish and English acted as an interpreter for Aidan.

The Easter problem presented itself to King Oswy, Oswald’s successor and who was married to Queen Eanfled of Kent. Oswy followed the Irish cycle, Eanfled the Kentish (Canterbury) one; sometimes two Easters were held in court in the same month.

Oswiu, as King of Northumbia called the Synod at Whitby in order to unify the date of Easter in Northumbria, but also to sort out the tonsure worn by his monks.

The Irish conversion of northern England brought with it rituals and calendars of the northern Irish church. At the same time, conversion in the south of England sponsored by King Edwin, from the 620s was aligned with the Roman clerics but was in real difficulty.

David Dumville said of the northern English conversion ‘monasteries were founded by Irish men, and the English continued to be pupils. They learned to read and write from the Irishmen: they were taught to read, write and speak Latin; they were instructed in all aspects of Christian faith and learning by Irishmen’.

St. Colmán, the bishop of Lindisfarne spoke for the Irish custom at the synod. Bishop Agilbert, a Frank who had studied in southern Ireland spoke for the Roman proposal. The king made the final decision and backed the Roman proposals even though Bede had failed to explain that Rome had switched from the Victorius calculation in favour of one from Dionysius Exiguus in 640AD. Colmán left Northumbria after the Synod of Whitby in disagreement and along with a group of his monks returned back to Ireland.

The Irish churches in Northumbria did not accept the Dionysian cycle until 716AD.

The Synod of Whitby was a set-piece debate between the northern Irish church and the Roman churches in Britain. This was a turning point in Irish ecclesiastical domination of northern England, particularly in Northumbria and beyond.

After the Synod of Whitby 664AD.

The Irish church had lost and the Irish attendees withdrew to Northumbria. Northumbria retained their old customs. Adomnán visited Northumbria in 658 and 688AD and persuaded them to adopt the Roman cycle. It wasn’t until 716AD that the monks of Iona accepted the decisions at Whitby for we read in the Annals of Ulster AU716.4 ‘The date of Easter is changed in the monastery of Iona’.

The Columbian houses in Europe which had been following their founder and the practices he had introduced were put under pressure to change their Easter calculation and they style of their haircut.

Strong reservations about Rome’s calculation of the Easter table continued into the 7th and 8th centuries with Rome making changes to the formula.

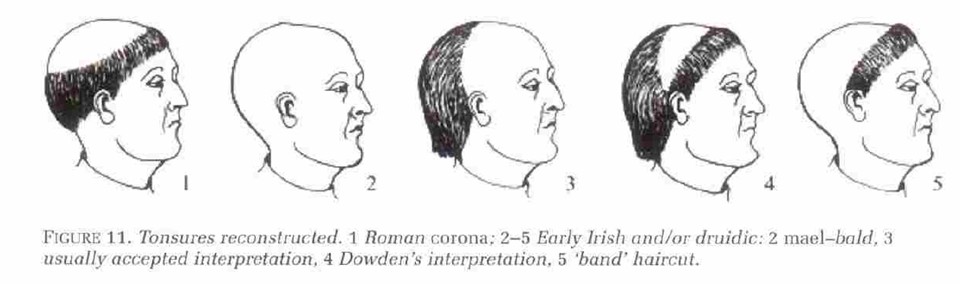

The Haircut.

The earliest Christian tonsure, practiced probably from the fourth century, consisted of shaving the entire head. The Roman tonsure appears in the 6th century and consisted in shaving the top of the head, leaving a circular band of hair in the form of a crown. By the 7th century the Roman tonsure had come into conflict with the Irish style. It is suggestion that the Irish tonsure was from ear to ear and although rejected at Whitby but survived for some time.

Bede does not give us any account of how the tonsure issue was addressed at the synod.

Image of haircuts